Thank you Adrian for the opportunity to address the IPA today.

I would like to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we meet today and pay my respects to elders past, present and future.

I would like to talk to you about three things today.

First, a review of the Federal Government’s Budget announcements and outline some of the policy rationale behind them.

Second, some thoughts on transport infrastructure spending from a macroeconomic perspective including reflections on recent commentary on the potential to increase infrastructure spending.

Third, a more microeconomic examination of transport infrastructure, in particular, discussion of developments in strategic planning, business case assessment, and intergovernmental cooperation.

Before I begin though, I’d like to discuss a new policy associated with my acknowledgement of the traditional owners.

An Indigenous framework

As part of a broader suite of Indigenous “Closing the Gap” reforms, the Australian Government has identified land transport as an area which can offer significant economic opportunities due to the scale, size and location of projects across regional and remote Australia.

The Government has embedded into a new National Partnership Agreement on Land Transport Infrastructure Projects, an Indigenous Employment and Supplier-use Infrastructure Framework.

The framework aims to increase economic opportunities for Indigenous job seekers and businesses in the delivery of government-funded land transport infrastructure projects.

Starting on 1 July 2019, state and territory governments receiving Commonwealth funding through the Infrastructure Investment Program must develop and submit an Indigenous Participation Plan for projects.

This includes setting out employment and business participation targets that reflect the local Indigenous working age population.

For example, employment targets will reflect the proportion of the working age population that are Indigenous in the area the infrastructure is being delivered.

Many companies have been highly successful in engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in work through programs similar to this one.

And I think this policy will provide a great opportunity to continue this good work.

The Framework builds on Indigenous participation initiatives already underway through the Infrastructure Investment Program, including implementation of Indigenous participation targets for the Northern Australia Roads programs and specific Indigenous employment initiatives relating to construction of the new Western Sydney (Nancy Bird Walton) Airport and Inland Rail.

A fine example of an infrastructure project achieving its Indigenous policy goals is the Great Northern Highway Upgrade - Maggie Creek to Wyndham project in Western Australia.

The project originally set out to achieve a 45 per cent Indigenous employment target however reached 50 per cent throughout the construction phase. This meant about 40 jobs created for Aboriginal people in the east Kimberley. Local Aboriginal businesses were engaged to provide labour supply, traffic control, site preparation and accommodation.

In addition, two Aboriginal trainees were engaged and four were identified in the surveying, administration, project management and construction management fields.

Up to six Aboriginal prisoners from the Wyndham Work Camp were engaged for upskilling, which helped ready them for re-entry to the workforce. The Commonwealth Government contributed $44.91 million towards the $56.14 million project.

The Commonwealth Budget

I now might move to the Budget which was brought down in April to accommodate the recent Federal Election.

Let’s start with spending proposals in the Budget and the 10 year pipeline.

In many ways, the decisions in the April Budget were the culmination of a process that started with the 2017-18 Budget.

In May 2017, the Government announced its commitment to a 10 year $75 billion infrastructure program. Of that $75 billion, around $50 billion was allocated to specific projects or programs.

In the following 2018-19 Budget, the Government allocated around a further $25 billion of the $75 billion.

This included $5 billion for the Melbourne Airport Rail Link, an additional $3.3 billion for Bruce Highway projects, and $280 million for the Central Arnhem Road Upgrade and Buntine Highway Upgrade in the Northern Territory.

In the recent April Budget, the Government boosted the 10 year program to $100 billion and allocated a further $23 billion.

This included: $3.5 billion to the first stage of the North South Rail Link to Western Sydney Airport; an additional $2.2 billion in national road safety funding through the Local and State Government Road Safety Package; $2 billion for Melbourne to Geelong Fast Rail; $1.5 billion towards the remaining sections of the North-South Corridor in South Australia; and $68 million for Tranche 3 of the Tasmanian Freight Revitalisation Program.

I think the establishment of the 10 year pipeline is a welcome development and has been seen as such.

It is important now that the 10 year pipeline rolls forward each year and steadily improves its alignment with key needs.

As part of this, the Government has committed to fund 20 business cases to support this pipeline.

This includes projects that the Government has already allocated monies against, as well as projects it can consider in future years.

The business cases will provide governments with an indication of the benefits and costs of projects and help maximise their effectiveness.

The move from a four year budgeting approach to a 10 year pipeline clearly makes a lot of sense for planning and for business.

And in framing the Department’s advice to the Government on the infrastructure program, the department drew on the IA priority and project lists, state priorities and our own extensive analysis.

The longer-term approach is present not only in the selection of larger projects, but also in some of the programs funded within the $100 billion.

The Australian Government has committed $4.5 billion to upgrade key regional freight routes through the Roads of Strategic Importance initiative, including $1 billion in additional funding in the 2019-20 Budget.

In the Budget, the Australian Government announced funding for 26 significant freight corridors and various specific projects across the country.

Works will involve rolling packages of upgrades to raise the standard of the full corridor, including feeder roads as opposed to just upgrading a single bridge or bottleneck.

This corridor approach will provide a more reliable road network, improve access for higher capacity vehicles, better connect regional communities and facilitate tourism opportunities.

Extensive stakeholder engagement was undertaken to establish this initiative, particularly in Northern Australia. This approach has been very well received by industry and state and territory governments.

A range of data was also used to inform the Government’s investment decisions by identifying and analysing current freight movements.

The Australian Government will continue to work closely with the state and territory governments to develop corridor strategies, and throughout the delivery phase.

Works will typically include, road sealing, flood immunity, strengthening and widening, pavement rehabilitation, bridge and culvert upgrades and road realignments.

Once completed, these will ensure that Australia’s key freight roads efficiently connect our regions to ports, airports and other transport hubs, which will deliver substantial social and economic benefits.

This corridor approach has been applied by governments to the Pacific Highway, with the completion of the Woolgoolga to Ballina section in 2020 to see the Pacific Highway duplicated from Hexham, near Newcastle, to all the way to the Queensland border.

It is being applied to the Bruce Highway with over $10 billion being committed.

And will now be applied to the Princes Highway starting with a $1 billion commitment, and the Newell Highway with a $400 million commitment.

These commitments are all supportive of the Government’s National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy.

There were a couple of smaller spending but significant announcements in the Budget that also support the strategy.

Freight data

The Government will provide $16.5 million to deliver data initiatives as part of the National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy including:

- $8.0 million for the National Heavy Vehicle Regulator to streamline the approval process for road access by heavy vehicles;

- $5.2 million for the design of a freight data hub, including arrangements for data collection, protection, dissemination and hosting; and

- $3.3 million for the establishment of a freight data exchange pilot to allow industry to access freight data in real time and a survey of road usage for freight purposes.

I’d like to thank Adrian and IPA for its important role in driving the data elements of the strategy.

At the Transport and Infrastructure Council’s next meeting, members will be asked to agree to the National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy and Action Plan.

Just as an aside, and predicting a question that I might get in the Q and A session, I might just mention another item that will be on the next TIC agenda.

Heavy Vehicle Road reform

This is an area that doesn’t seem exciting to many but an area that represents an opportunity to extend to road infrastructure some of the market features that are already present in other infrastructure markets such as water, gas, electricity, telecommunications, and in transport infrastructure, the aviation and maritime sectors.

A road user charging approach already exists for heavy vehicles; however, current arrangements are not serving industry or governments well. Governments are working to improve these arrangements through Heavy Vehicle Road Reform.

Heavy vehicles account for around 3 per cent of the vehicle fleet and 8 per cent of total kilometres travelled in Australia.

Heavy Vehicle Road Reform is a good example of microeconomic reform. It is about creating stronger links between road usage, road-related charges and services for road users. It aims to drive productivity through two key outcomes:

- A better return for industry – road user charges paid by heavy vehicles will be directed to investments that boost industry productivity, support safer roads, back economic growth across our regions and drive efficiencies.

- Improved efficiency for governments – better understanding of industry needs will support better investment decisions. Greater funding certainty will support investment planning and more effective maintenance.

Reforms have been recommended by multiple expert reviews; all governments have been working together on this and making solid progress since 2015. Industry is supportive of better governance arrangements around investments and decision-making.

The Commonwealth, states and territories, the Australian Local Government Association and the National Transport Commission are working collaboratively in progressing the reforms. Governments will further consider these reforms later this year.

There is great potential to draw lessons from Heavy Vehicle Road Reform for governments’ future considerations of broader road reforms.

Some macroeconomic perspectives on transport infrastructure

Australia has growing land transport infrastructure needs across road, rail, ports and airports driven to a significant degree by our strong population growth.

Our population grew by 17 per cent over the past decade, more than double the OECD. Two thirds of the population growth was in the three largest population areas: Sydney, Melbourne and South East Queensland.

For our capital cities, the costs of congestion were estimated by BITRE to be around $25 billion a year in 2017-18 and are projected to increase to $40 billion by 2030.

Investment in ports and airports is primarily being addressed by the private sector, with the significant exception of Sydney’s new Western Sydney International (Nancy Bird Walton) airport.

In road and rail, it is predominantly a public infrastructure story. The following charts illustrate the story.

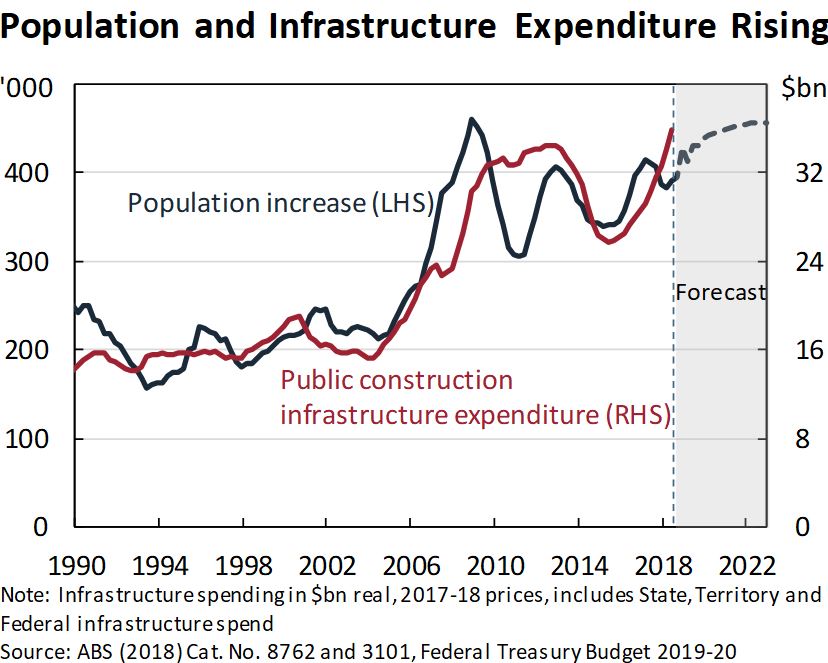

Chart 1 shows the increase in population and associated increase in public construction infrastructure expenditure. This is all infrastructure including transport, communications, water and electricity.

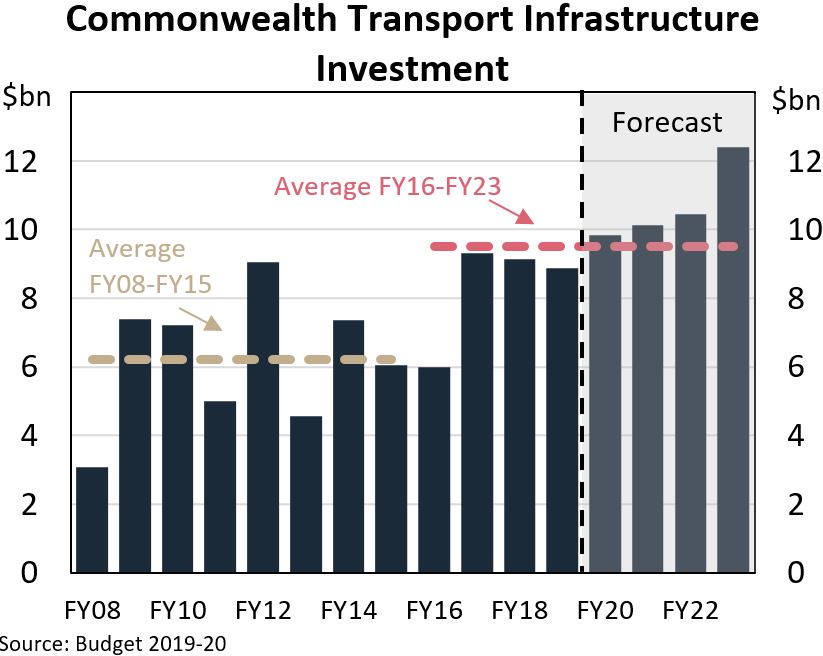

Chart 2 shows the increase in Commonwealth transport infrastructure expenditure and roughly speaking the lift to around $10 billion a year in infrastructure expenditure, in line with the pipeline discussed earlier.

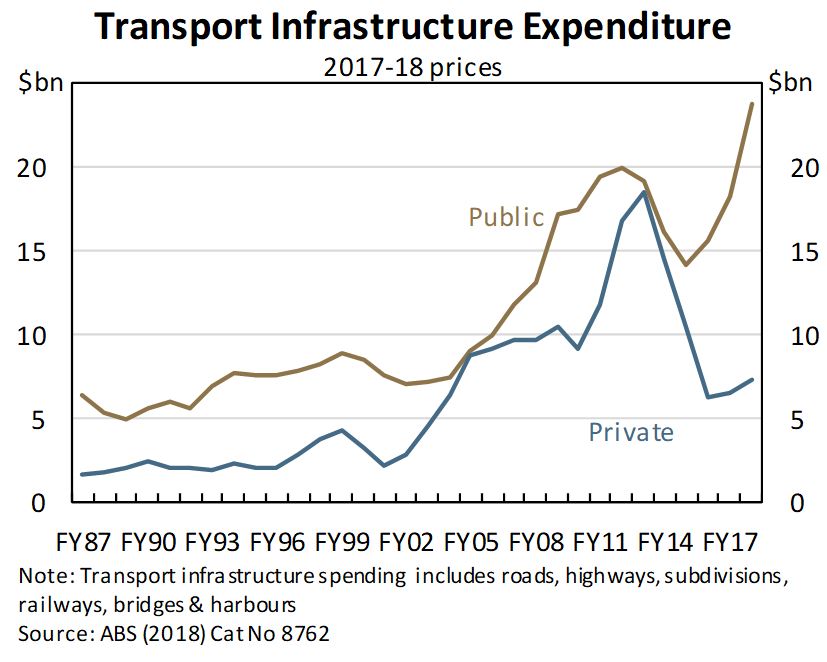

And chart 3 shows the recent increase in public transport expenditure and the sustained lift in private transport expenditure.

Chart 1

Chart 2

Chart 3

If we look forward, we can see that infrastructure expenditure is expected to continue to increase.

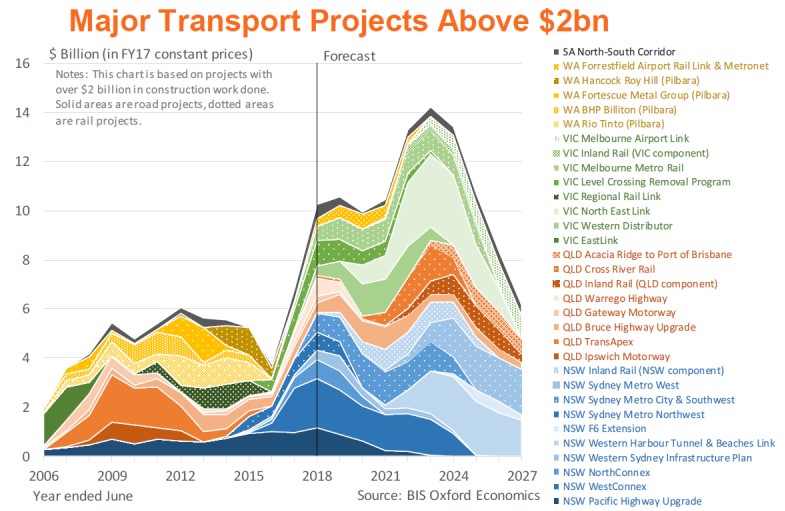

This chart (Chart 4) put together by BIS Oxford, which many of you are familiar with, shows the significant increase in activity expected in coming years.

Chart 4

The significant projects underpinning this activity, done right, represent a real opportunity to improve the lives of Australians.

Despite this significant increase in activity, there are calls for more infrastructure spending including transport infrastructure.

And this is despite concerns about infrastructure activity indigestion, especially in larger cities, with the public disrupted in their day-to-day activities by many large projects.

Some of these calls represent cheering for the sector where one gets the sense there could never be enough spending on infrastructure!

However, where there are calls for more spending that is new, these represent both current macroeconomic circumstances and the important role infrastructure plays in enabling a more productive economy.

For example, Dr Philip Lowe – RBA Governor – recently discussed the key role public infrastructure investment is playing in supporting macro-economic demand.1 Indeed IMF research suggests the ‘multiplier effect’ of infrastructure investment may be higher in a low interest rate environment.2

In the short run, building infrastructure generates economic activity, creating employment and incomes earned by workers and profits for firms.

This stimulus effect is a common feature of all infrastructure including social infrastructure like hospitals and schools.

So the short-term economic benefits are not unique to transport.

Nevertheless, it is worth thinking through the opportunities for public transport expenditure should, for example, international downside risks eventuate, the domestic economy weakens and policy makers become interested in responding with increased spending.

Often, the response in these circumstances is to suggest bringing forward existing projects, including large projects.

This is not out of the question in our current circumstances, but challenging in light of the record spending I outlined earlier.

In fact, it is challenging to bring large projects forward even when spending isn’t so high.

Large projects and good project management requires forward planning and significant coordination across many activities.

The timing challenges of large projects means they are not easily part of macroeconomic management.

There are benefits of course, to maintaining a significant pipeline of large projects for the confidence effect this gives businesses, and the incentive for them to maintain and increase their workforces despite weaknesses elsewhere in the economy.

And maintaining a significant pipeline does provide more flexibility around delivery, even of the larger projects.

The other feature of large projects is that they are like all infrastructure projects, delivering most of their benefits, especially from a demand perspective, locally.

I’ll return to this issue later in my presentation.

In a situation where there is a generalised slowdown in activity, the ideal fiscal response is one that is generalised, including from a spatial perspective.

What am I getting at talking about a spatial perspective? Well for infrastructure, it is spending that occurs across the country in regions and cities.

An opportunity in transport infrastructure to provide a relatively quick and generalised support to demand is through a step up in maintenance expenditure.

Moreover, this may be a no regrets policy choice by which I mean even if the fiscal response was not needed, the increased spending would deliver significant productivity returns.

Recent work by BITRE on the economics of road maintenance shows, not surprisingly, that deferred expenditure on road maintenance due to unduly constrained maintenance budgets, ultimately leads to high costs.

The research also shows that when moving to a more optimal flow of maintenance expenditure, there is usually a significant spend required in the earlier years to effectively catch up to the optimal profile.

I’m not certain how profound this issue is in Australia and more work would need to be done to calibrate such a policy, but from conversations with my colleagues in the States, I suspect we have at least some opportunity.

And while the maintenance expenditure would typically be targeted at more trafficked roads, it is likely to be reasonably disperse in nature and provide good generalised support to the economy.

Maintenance is also more labour intensive than large-scale construction, so spending impacts more domestically.

Moreover, the likely road safety benefits of improving existing regional roads would be high.

Similar opportunities might also exist in improving the quality of rail infrastructure through enhanced maintenance programmes.

And it may extend to smaller projects, and even in part, to proposals to increase the speed of trains to population centres lying around 100km from our major cities.

A key element of all of these expenditures from a macroeconomic policy perspective is the speed at which the expenditures take place if, and when, they are required.

The types of activities I’ve been describing, typically don’t require planning approvals, land acquisition, environmental approvals and many are already on the books of state transport departments.

In other words, monies can flow significantly more quickly than for new road and rail projects.

One quick final comment on transport infrastructure from a macroeconomic perspective.

Interest rates are clearly very low at the moment both here in Australia and globally.

Government bond rates are low as are risk premia.

This has implications for the appropriate discount rate in evaluating infrastructure projects.

In Australia, project costs are typically evaluated at 7 per cent and 4 per cent real discount rates, with 7 per cent typically presented as the base case.

I would note that at 7 per cent real, Australia would have one of highest base case discount rates in the world.

Using a lower discount rate as the base case would have some implications for project selection, although perhaps not as much as some would expect.

It also potentially has implications for the size of infrastructure programs.

The importance of project selection would not in any way be diminished in the face of decisions to expand infrastructure programs.

Undertaking more projects or increasing expenditure still requires the right projects to be built at the right time and in the right place.

Some microeconomic perspectives on transport infrastructure

Let me now shift from the discussion of infrastructure spending from a macroeconomic perspective to a more micro or project decision-making lens.

One the benefits of the emerging stability of long-term infrastructure budgets, be it through the rolling 10 year Commonwealth Budget approach, or through similar approaches being taken by many of the states and territories, is that it enables policy makers to focus more intently on planning and prioritising the right projects.

That is, how to optimise infrastructure decisions given a budget envelope, rather than significant energies year after year, going in to establishing the budget envelope.

Of course infrastructure should compete with all other public spending in governments determining their budget, but the nature of infrastructure investment necessarily entails that this be married with a long-term approach or the requisite planning will never take place in the face of the uncertainty around the funding envelope.

Moreover, it provides a more stable environment for businesses to invest, including in people and their skills.

How then to make good decisions about infrastructure investment?

There are many elements to this. I’d like to consider just three of them today. And they are:

- Having a long-term plan

- Rigorous cost benefit analysis of individual projects

- Close working relationships across all governments

Long-term plans

A number of jurisdictions have developed, and in some cases updated, their long-term plans. A welcome development is the integrated nature of many of these plans across transport, settlement or population and land use more generally.

I remain a big fan of further integrating these plans across the three levels of government.

Occasionally, I hear concerns that this blurs lines of responsibility between the State and Federal Governments. My experience with the Western Sydney City Deal is in fact the opposite; it actually clarifies responsibilities and provides a basis for local and state plans to be more effectively reflected in Federal spending decisions.

The announcement of City Deals for South East Queensland and Melbourne will provide the next test for the effectiveness of this approach.

The Federal Government in the run up to Budget released its population plan, Planning for Australia’s Future Population. The Plan and a National Population and Planning Framework should contribute to more integrated planning and efficient investment.

City Deals are one element of the Government’s broader population plan.

The National Population and Planning Framework is being led at the Federal level by the Treasury department.

The principles that underpin this exercise are:

- Collaboration

- Transparency

- Long-term planning

- Community focus

The Centre for Population will help all levels of government and the community better understand how national, states, cities and regions’ populations are changing and the opportunities and challenges that arise.

The Government recognises that population changes have broad-reaching effects across the economy and society.

Population growth should not be a side effect nor after thought of other policies. It should reflect an active and deliberate approach, with governments working together.

This process marks a turning point in the way population is treated across government, with a move to greater collaboration, transparency and longer-term planning.

To support these developments in population policy, the Government has also announced a new National Faster Rail Agency and a $2 billion commitment to help deliver faster rail between Geelong and Melbourne.

The National Faster Rail Agency will be established from 1 July 2019 and have a number of functions including the following:

- lead the development and implementation of the Australian Government’s 20-year plan for a Faster Rail Network;

- oversee the development of business cases with state and territory governments, ensuring that population and transport policy objectives are met; and

- identify additional rail corridors that would benefit from faster rail services over the long-term, in consultation with state and territory governments, industry and stakeholders.

The National Faster Rail Agency will be supported by an Expert Panel.

Among other things, the Expert Panel will provide advice to the Minister for Population, Cities and Urban Infrastructure and to the Agency on faster rail, transport demographics and economics to inform project identification and delivery, service requirements and operating standards.

The Agency and Expert Panel will also be directed to provide advice on the opportunities for future faster rail business cases, including Sydney to Canberra and Melbourne to Bendigo and Ballarat.

There is now funding to support five new faster rail business cases including:

- Sydney to Wollongong;

- Sydney to Parkes (via Bathurst and Orange);

- Melbourne to Traralgon;

- Melbourne to Albury-Wodonga; and

- Brisbane to the Gold Coast.

These commitments build on business cases underway for Sydney to Newcastle, Melbourne to Greater Shepparton, and Brisbane to the regions of Moreton Bay and the Sunshine Coast, and will provide an excellent foundation for future infrastructure program funding.

Rigorous cost benefit analysis of individual projects

Business cases and their associated Benefit-Cost Ratios are an important element in government decision making.

Funding the highest priority infrastructure projects is essential for Australia’s economy and standard of living.

And scepticism about how projects are selected weakens public support for large-scale investment in infrastructure.

There is no substitute for rigorous and transparent cost-benefit analysis.

I spoke briefly earlier about an element of measuring the costs of infrastructure projects, discount rates, and now I’d like to talk a little about the benefits.

Some obvious examples of benefits are safety and maintaining regional social equity/service standards.

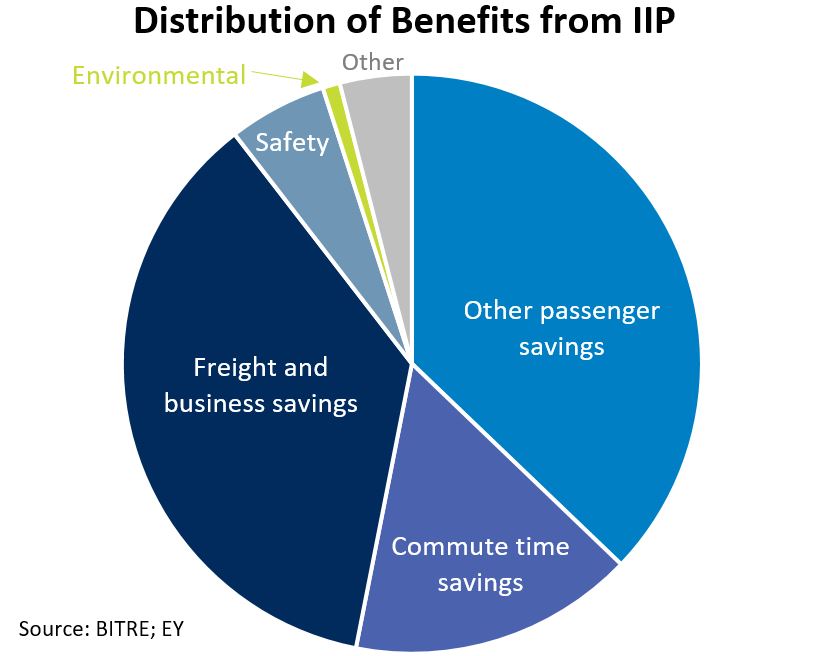

Source: BITRE; EY

For example:

- Since the broader Bruce Highway Upgrade Program commenced, there has been a 31 per cent reduction in crashes, a 32 per cent reduction in fatalities and a 28 per cent reduction in injuries along the Bruce Highway in Queensland.

- Since the start of the Pacific Highway upgrade in New South Wales, the number of fatal crashes has halved, down from more than 40 each year to about 20 annually in recent years.

Over a longer horizon, the economy benefits from a larger capital stock and higher productivity.

For example, exports may be facilitated by the construction of an airport, safety may be enhanced by a better quality highway, job access boosted by better rail links and so on.

- Research suggests three broad benefits for producers:

Reduced transport costs

Lower transport costs in terms of fuel, wear and tear, and time means lower production costs. The benefits vary by industry, but are largest for those transporting goods over long distances. - Greater access - enabling scale economies and competition

Access allows scale economies because one firm can service bigger markets. It also facilitates trade between locations opening up competition and allowing firms to specialise. - Decreased inventory costs

Reduced time and travel costs allows centralised firms to service distant markets without the need for regional storage hubs.

The community also benefits

- The reduced production costs above result in reduced costs of goods and services for consumers.

- The community and workers also enjoy reduced travel time and greater access to jobs and services.

Recent analysis of the business cases underpinning the Commonwealth Infrastructure Investment Program suggests most of the economic benefits are due to this last element - lower travel time and greater access for the community (Chart 5).

Chart 5

With local benefits dominating most projects, it is hardly surprising that there is constant pressure on infrastructure decision making from the spatial features of our democracy.

All the reason that infrastructure decision making ensures we get the right projects, in the right places, at the right time in the national as well as local interest.

Working closely with State partners

It goes without saying that all levels of government must collaborate effectively to deliver the infrastructure Australia needs.

The states and local government are closest to the ground, the subsidiarity principle.

The Federal Government needs to work closely together with relevant state and territories as business cases for initiatives are developed, to determine the optimum funding and delivery structure.

In establishing the policies and priorities I have spoken about today, we have listened closely to our state and territories colleagues, taken their advice and respected the expertise, which is deeper and beyond that at the Federal level reflecting their responsibilities.

I would like to acknowledge the highly constructive relationships I have observed between state and territory and Commonwealth officials.

Of course we don’t always agree, but the open exchange of information and contest of ideas puts us in a good position to serve our respective governments.

Conclusion

There is a bit going on in infrastructure policy at the moment.

A lot more than I can cover today including technological developments which have the ability to significantly improve the productivity of existing assets as well as introduce new services. Drones would be one such example.

In this context, it is important to remind ourselves that infrastructure in the long-run is not so much an engine of growth as an enabler of growth.

But for this to be true, especially in those areas of infrastructure where there is an absence of a market, projects need to be rigorously assessed, carefully designed and appropriately timed.

Thank you for the opportunity to speak to you today.

1 https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2019/sp-gov-2019-05-21.html

2 https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/TNM/Issues/2016/12/31/Fiscal-Multipliers-Size-Determinants-and-Use-in-Macroeconomic-Projections-41784