National financing authority for local government—options assessment PDF: 1699 KB Executive summary

Local infrastructure is the backbone of our communities and our regions. Providing and maintaining this infrastructure is one of the most important responsibilities faced by Australian councils, but it also presents one of their largest challenges.

Strong Foundations for Sustainable Local Infrastructure, the Ernst & Young report launched by the Australian Government in June 2012, suggested that there is a suboptimal use of debt finance within local government which is contributing to an under-provision of infrastructure by the sector. Building on recommendation 3 of the report, Ernst & Young has been engaged to develop this finding further.

The objectives of this study are:

- to test the strength of the case for federal and state/ territory government representatives to support an initiative which aggregates the debt finance sought by the local government sector

- to identify a set of feasible models for debt aggregation (including models for a collective financing vehicle), explore the relevant design issues and select and develop the preferred option(s).

The case for action

National local government financing vehicles operate effectively in a number of countries, and in some cases have been in existence for over a century. In other countries where they do not currently exist, notably France and the UK, planning is relatively advanced.

Precedent alone does not justify change in Australia. Indeed, it is widely acknowledged that Australian councils already have good access to debt finance, in the form of bank credit or—in some jurisdictions—loans from treasury corporations or a collective vehicle.

But the fact remains that councils in Australia are not taking advantage of the opportunities they have to use debt as a resource to contribute to the growing infrastructure task. They continue to think that borrowing is "bad", it is too expensive, and that it introduces significant financial risk that they are unable to manage.

We do not underestimate the risks and costs that come with debt. Nor are we in the business of telling councils that they must borrow more. However, we do see a strong case for offering councils greater confidence in accessing finance at the best possible rates and the same opportunities that other governments enjoy in terms of tapping into a pool of institutional investment that is hungry for low-risk credit products.

The incentives for intervention include:

For the Commonwealth:

- encouraging the local government sector to manage its own future and contribute to local and regional economic prosperity and community wellbeing

- using its unique status to bring together diversified stakeholders, make the case for reform and provide support and direction for policy intervention.

For state and territory governments:

- supporting councils as they continue towards financial self-sufficiency and ultimately reduce their reliance on their state and territory supervisors

- contributing to policy goals around asset management, capacity building and financial sustainability in the local government sector

- maintaining oversight and legislative supervision of the sector within each jurisdiction.

For local government:

- retaining the responsibility for delivering infrastructure and decision making on the best use of available funding

- pooling their requirements and collective creditworthiness (supported by the implied backing of the states and territories) to create the critical mass needed to issue financial instruments into the capital markets

- accessing lower arrangement and servicing costs for debt products

- accessing the support of specialist resources and market expertise

- using responsible borrowing to deliver infrastructure priorities sooner and more efficiently, while sharing the costs amongst all beneficiaries.

Recommendation

Strong Foundations for Sustainable Local Infrastructure suggested that a national collective financing vehicle for the local government sector could assist address the suboptimal use of debt in the sector by:

- providing easily-available and competitively priced debt to the local government sector by aggregating risk and supply across many councils

- increasing the pool of finance by offering structured products to the institutional investment market, hence establishing a conduit between councils and capital lenders

- encouraging a cultural shift away from the reluctance to borrow

- enforcing governance and reporting arrangements to ensure the sustainability of councils is not jeopardised

- providing financial and legal assistance and expertise to those councils with limited in-house capacity.

Importantly, a national collective vehicle must be designed so that it achieves these objectives with a minimal impact on the relationship between the local government sector and the Commonwealth, states and territories.

It will be an "enabling" organisation, with a role of giving councils access to cost-effective debt, without forcing them to take it on where not appropriate or desired. Nothing about the organisation should take away from each and every council the responsibility for sound financial management and decision-making.

There are a number of different models for collective financing vehicles overseas. We have evaluated a long-list of 11 options which satisfy the broad requirements set out above but are distinct by virtue of different permutations of factors of ownership, the providers of any credit enhancement and the nature of any credit enhancement. The evaluation criteria applied address the key success factors around purpose and function, impacts on other governments, market credibility and participation rates.

The option which scored highest in the evaluation represents a tailored structure which we believe would be suitable to the unique Australian landscape:

The preferred model is a collective financing vehicle established by a group of councils with the objective of issuing debt securities to the capital markets and on-lending the funds to members. It has the following features:

- The authority would be an incorporated entity established and controlled by the local government sector and would operate under a voluntary membership arrangement.

- Each member would be required to provide a minimum amount of capital which could for example be proportional to average rates revenue. Capitalisation of the authority would satisfy ongoing capital adequacy requirements and could fund establishment costs including any losses in the early years.

- Each member would be required to implement a mutual guarantee over the authority's liabilities, which would be capped in proportion to its financial position or level of borrowing from the authority.

- There would be no explicit credit enhancement provided by the Commonwealth, states or territories.

- The authority would aim to achieve the best possible credit rating, which would be based upon the combined creditworthiness of participating councils, strong integral liquidity arrangements, the mutual guarantee provided by members, and the implied support of the local government sector by other tiers of government.

- The liquidity and mutual support provisions would ensure that the likelihood of step in by state/ territory governments would be extremely low, thus minimising the amount of financial risk that states/ territories would have to take on in return for their continued implied support of the local government sector.

- The authority would build a presence in the bond markets and issue debt securities to raise funds.

- The authority would provide targeted debt products to its members at cost-effective interest rates and with flexible terms. It would develop a suite of policies to govern access to lending based upon the capacity of each applicant to repay the amount of debt sought.

- The authority would provide advice to its members on the process for accessing debt and related financial products, and other services related to councils" capital structuring.

- The authority would be incentivised to keep its cost base low, rather than to achieve a profit.

In identifying a preferred option, we acknowledge that the evaluation undertaken suggests that several models are closely ranked. This outcome largely reflects the broad similarities among the commercial characteristics and structure of the options. Some features and benefits are, as a result, found in all the options identified. These include the potential to provide financial benefits, for those entities which borrow, in the form of lower arrangement and servicing costs, and the potential to stimulate a higher rate of investment in priority projects which produce positive economic, social and/or environmental outcomes.

However, the evaluation process suggests that marginal differences in the credit support structures and the proximity to councils could have a significant impact on stakeholders and processes.

The following factors, when combined, were crucial in differentiating the preferred option from other options, and demonstrating a benefit when compared to the status quo:

- Cost-effective debt finance

The preferred model has the potential to achieve pricing outcomes which represent material savings compared with the estimated borrowing costs of many councils.

- Promoting a culture of sustainable debt use

The preferred model could contribute positively to promoting a culture of sustainable debt use.

- No explicit support from other tiers of government

The preferred model does not require explicit credit support from other tiers of government and is unlikely to require substantial legislative change. These are important factors in measuring the cost—including time—and risk inherent in a subsequent implementation process.

International precedents

In developing the case for a national financing authority in Australia, there are a number of lessons that can be learnt from international experience. In particular:

- New Zealand has the most recent experience of establishing a collective financing agency for local government. The New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency was incorporated in December 2011. With nine founder members, it now has 30 councils as members. It has already released 10 bond tenders, raising in excess of NZ$1.5 billion, and consistently achieving highly competitive margins over New Zealand Government Bonds. Standard & Poor's and Fitch have both assigned the agency a domestic currency rating of AA+ (the same as the New Zealand Government) and the outlook on these ratings is stable. The New Zealand Government does not explicitly guarantee the agency's liabilities.

- Local government in Scandinavia has a long history of using the services of a collective financing vehicle—Denmark's agency has been operating since 1898. While each has different structures and established relationships with other tiers of government, these can provide some important lessons for Australia. In Sweden, for example, the three largest municipalities (Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmo) are not members of the collective financing vehicle, but it has still been able to function extremely well for a number of years. This demonstrates that a critical mass might be achievable even without the participation of the very largest councils.

- In Canada, the Municipal Finance Authority of British Columbia (MFA) is a good example of the mutual guarantee model. Local governments within each regional district are joint and severally liable for each others" long-term debt borrowings through the MFA. When a municipality passes a borrowing bylaw and presents it to its regional district for the purpose of issuing security, all municipalities in the region must vote on their acceptance of the borrowing. Approval of the bylaw binds each municipality with joint and several obligations.

- In France, a local government financing authority is currently being established, and the UK Government is also considering the case for action.

Throughout this report there is a strong focus on identifying and capturing the lessons from overseas. A comparative analysis of the international agencies is provided in Appendix D.

Next steps

Moving to the next stage of development will need a concerted effort by all tiers of government. If there is appetite to take this initiative forward, we anticipate that the next steps should be:

- policy consultation with federal, state and territory stakeholders

- further commercial and legal investigation of the preferred option, including consultation with the local government sector to test demand

- identifying commitments, costs and resources to move into the ‘build’ phase.

We recognise that the establishment of a national financing authority for local government would be a considerable challenge.

Firstly, a national financing authority will only succeed if a minimum number of councils are minded to join it. A critical mass would be required to give the authority the buying power in the market to raise funds and pass on capital to councils at low interest rates.

Secondly, the idiosyncrasies of the Australian federal system, the different conditions and arrangements in different jurisdictions, and the multitude of stakeholders, mean that the path to reform has many obstacles.

However, we urge the Australian Government to continue to work with jurisdictions and local government on this initiative. Providing the apparatus for councils to develop the same market presence and fund raising capacity as other governments could present a real opportunity for the sector to move to an optimal debt load and ultimately reduce the substantial backlog of priority infrastructure projects which create and sustain amenity in local communities.

This objective is, we believe, consistent with the vision for strong and sustainable Australian councils which is shared by all tiers of government.

1. The case for action

This section provides context to the recommendation for a national financing authority by identifying and substantiating the case for action. In particular, it:

- articulates and validates the problem identified in Strong Foundations for Sustainable Local Infrastructure, namely that the suboptimal use of debt in the local government sector is having a negative impact on the ability of councils to address the growing infrastructure task

- explains that the lack of scale and coordination within the sector is preventing the participation of private investors, who have a demonstrated appetite for low-risk highly-rated debt instruments

- demonstrates how a national financing authority for local government could provide a solution to the problem

- identifies key features and considerations which we believe to be "prerequisites" for a future national financing authority in Australia if it is effectively to address the problem.

The analysis in this section is developed further in Appendix A.

Debt and the infrastructure task

Local infrastructure is the backbone of our communities and our regions. Underinvestment in this infrastructure results in constrained economic activity, reduced amenity for communities and declining social equity. But the costs of infrastructure are high and lumpy, and at a time when there are many competing demands on revenues, meeting these costs places significant pressure on council budgets.

Leveraging core revenue sources to access debt is an option open to all councils as a means of contributing to the significant upfront costs common to most infrastructure projects, and can be the difference between a project going ahead or not.

Borrowing is a common feature of private sector capital structures and does not mean that a council is acquiring things it cannot afford. Rather, in the context of sound financial management and project planning, the key benefits of debt are that it can:

- enable councils to deliver new infrastructure when it is required and earlier than they otherwise would have been able

- allow the smoothing of the payments for new investment over time

- prevent the need to divert funds from internally-generated renewal and maintenance budgets to capital expenditure

- enable councils to invest in the renewal and lifecycle costs of existing infrastructure, which are time-sensitive and if not delivered can increase the whole-of-life cost of an asset

- allow the cost of infrastructure to be shared with future generations who will enjoy the benefit of the asset

- open the door to new sources of investment, for example from institutional finance providers, which bring additional rigour and discipline.

Overlooking debt as a source of capital can prevent infrastructure investments from going ahead because councils often do not have adequate alternative resources to fund projects with lumpy cost profiles. The consequence of delay and non-investment is that the infrastructure gap gets bigger—or at the very least, it does not get smaller—and the local government sector's capacity to deliver economic, social and environmental benefits and contribute to national productivity, is significantly weakened.

Debt in the context of local government funding

Debt is a source of finance, and it is important to understand that this is not the same as funding.

Funding is how infrastructure is paid for. Finance describes the money that has to be raised upfront to deliver the infrastructure, and—unlike funding—it needs to be repaid. In other words, infrastructure must be funded, irrespective of how it gets financed.

This means that while financing can support funding, it is ultimately a secondary consideration. Local infrastructure is (and will remain) funded by the community through taxation and user charges and revenues received from other tiers of government. Meeting the infrastructure task will always be dependent upon the quantum of this funding. Additional finance may make possible individual projects or programs when funding is constrained, but it is not the solution to the underlying issues of sustainable funding.

But while financing will always be dependent upon funding, it can be crucial to the timely delivery of key community infrastructure projects. Debt finance enables councils to deliver infrastructure earlier than they otherwise would have been able and to spread the costs amongst future generations who will enjoy the benefit of the investments.

The suboptimal use of debt

It is widely acknowledged that most Australian councils do have access to debt finance, either in the form of bank debt or services provided by the state/ territory government or an existing collective agency—and hence there is no demonstrable failure of the market to provide finance.

But the fact remains that—as a general rule—Australian councils continue to adopt a cautious approach to borrowing. There remains a clear reluctance to borrow as an appropriate method of paying for infrastructure. Most councils prefer to use current year funding in the form of rates and grants receipts for this purpose, rather than utilise debt finance to match the incidence of the costs to the benefits, and ensure that current ratepayers are not shouldering a disproportionate burden.

This is caused in part by an information asymmetry between councils as borrowers and the providers of finance that arises because councils often do not have the background and skills to make informed judgements about the risk of borrowing. The evidence of the reluctance to borrow supports the view that councils make an overly pessimistic assessment of the risks of using debt, despite possessing what lenders clearly consider to be sound credit fundamentals.

Related to the information gap is the fact that the local government sector does not currently have the tools to tap into or create an interface with the institutional investment markets. Most Australian councils are relatively small entities and as such get less "attention" from capital markets than, say, state or territory governments or large corporations. And because they issue debt in a fragmented way and typically in relatively small quantities, the costs incurred are significantly greater than would be the case if there was the opportunity to work together.

Aggregation as the key to unlocking the markets

A targeted policy intervention is required to facilitate the introduction of additional private capital into the local government sector and to enable the reluctance to borrow to be overcome. A coordinated effort by all tiers of government is necessary to spread awareness of the implications of unduly low levels of debt for councils" ability to invest in their assets.

The central objective of action should be to assist the aggregation of the smaller borrowing needs of councils through a collective vehicle, which would develop a communal buying power and the required security to gain a strong credit rating. This in turn would enable councils to access lower cost borrowings, while also introducing operational efficiencies and administrative synergies to drive costs down.

In current market conditions, there is likely to be a strong demand for low-risk government or quasi-government instruments, which a collective vehicle would be able to satisfy by issuing bonds into the capital markets, and on-lending the proceeds to participating councils.

Providing access to debt in this way is not to say that every council should participate and should be seeking to increase its borrowings and financial gearing. Ultimately the capacity to raise debt will be a function of the capacity to fund debt servicing payments for the term of the loan, and to repay the principle once the term has expired. It must never be forgotten that the availability of finance will always be a secondary consideration to the availability and application of funding.

Towards an Australian national financing authority

If it is to fulfil this role and bring substantive benefits to the local government sector, there are some overarching principles, design features, or prerequisites, which are inherent in accessing wholesale finance markets and must be present in a national financing authority for Australian local government.

These features (articulated below and in more detail in Appendix A), should be present in any option taken forward for further consideration.

- Purpose

The purpose of the national financing authority would be to pool the borrowing needs of participating local government bodies and fulfil them by issuing financial instruments.

The principal role of the authority would be to obtain cost-effective finance for its members, and not to ‘pick winners’ or take responsibility for investment decisions. Importantly, the availability of new debt products should not dilute the responsibility or incentives for councils to mitigate the risks of delivering specific infrastructure projects. As such, councils should remain focussed on managing their levels of financial risk.

- Ownership and governance

The national financing authority should be a corporatised entity in public sector ownership and should have clear lines of accountability to the participating local government entities. There will be a role in the governance structure for the state/territory governments, potentially the Commonwealth, and independent experts to ensure and demonstrate the competence and procedural rigour built into the authority's structures and processes.

The national financing authority would need to comply with all legal obligations including those related to the Corporations Act, National Competition Policy and state and territory local government acts. In issuing financial products and instruments, the national financing authority would be required to comply with the regulatory requirements of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) and potentially the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA).

- Membership and participation

To receive any services from the national financing authority, a council would need to become a member. Membership would not represent an obligation to use the authority exclusively, and members would retain the right to source services and finance from other entities including banks (subject to any restrictions imposed by state or territory legislation).

Membership should be voluntary. Any council could choose to apply to be a member, and equally, could choose to leave the authority. Ultimately, individual councils need to make their own evaluation of the overall benefits of membership.

As membership of the national financing authority would be voluntary, the number of participating entities would be expected to fluctuate over time as individual councils consider their own case for membership. Precedent authorities overseas have been founded by an initial group of members and expanded over time. The stability of the organisation will be a function of the level of "skin in the game" taken on by members, and the incentives provided to continue participation.

A minimum level of participation in the national financing authority is likely to be important because its ability to generate benefits will depend upon achieving a critical mass to provide an attractive proposition for inward investors. This means not just joining the authority but doing so with the intent of making use of the facilities available, possibly via a commitment similar to the one undertaken by founder members of the New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency.

- Intergovernmental considerations

The structure and role of the authority would need to be consistent with Australia's unique structure of government and sensitive to the concerns and needs of multiple stakeholders. These stakeholders will rightly need to be persuaded of the need to support the initiative, which will be a function of their understanding of the benefits and the risks, including implementation considerations, outturn set up costs and longer-term impacts.

We contend that ultimately the motives for supporting the objectives of a collective entity are consistent with the policy intent of the Commonwealth and jurisdictions to promote a self-sustaining local government sector that is capable of leveraging its "own-source" revenues to deliver the community's infrastructure requirements, while reducing its reliance on other tiers of government.

A national financing authority could create the conditions to help councils invest their own revenues in much-needed infrastructure projects and accelerate their journey toward financial sustainability. It would give further momentum to initiatives to promote capacity building, financial self-sufficiency and consistency of standards in local government. These initiatives reflect the objectives of the Commonwealth and all jurisdictions to help the sector grow and prosper.

- Functions

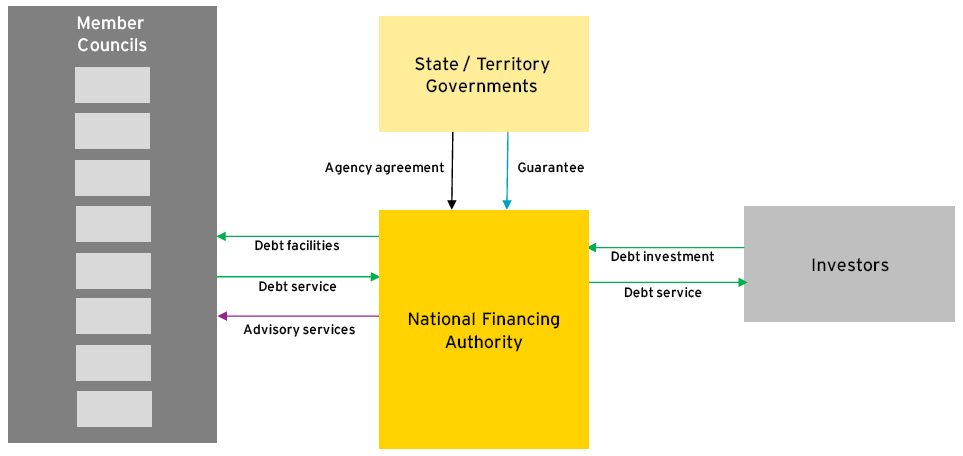

The national financing authority would have four primary functions: lending to local government, fund raising, supporting liquidity and credit quality, and providing advisory services.

1) Lending to local government

The national financing authority would provide targeted debt products to its members at cost-effective interest rates and with flexible terms. It would aim to become the "natural choice" for it members when it comes to borrowing.

The key features of the authority's function as a lender would be:

- Low cost: the authority would deliver low borrowing costs for its members, which would be set at a level sufficient only to fund the repayment of securities, cover the costs of the authority (including issuing costs) and accrue a prudent reserve.

- Equitable: the same low costs would be available to all members. This would mean that small councils wanting to borrow smaller amounts would be able to access the same interest rates as large councils with larger requirements.

- Responsible: the authority would develop a suite of policies to govern access to lending and provide a framework for a loan request acceptance process. This would incorporate components of the credit approval processes used by commercial banks and other public sector financing agencies.

2) Fund raising

The national financing authority would build a presence in the bond market and issue debt securities into the capital markets to raise funds on behalf of councils. In doing so, it would achieve what individual councils are currently unable to—namely bundling smaller debt requirements into larger bond issuances, pooling the needs of the sector and creating a consolidated and strong creditworthiness.

It is anticipated that the national financing authority would create a new class of highly rated bonds targeted at banks, insurance companies and super funds. Market consultation indicates that there could be considerable appetite for these instruments as they would be seen to be relatively low-risk investments, because councils enjoy steady and secure income streams in the form of rates and untied or general purpose government grants, which can be used to meet debt servicing obligations and to secure debt facilities.

Funds raised would be held by the entity for the purpose of lending operations, maintaining liquidity through reserves or other treasury instruments, and operating expenses.

3) Supporting liquidity and credit quality

Adequate credit support arrangements would be required to satisfy the concerns of investors around the ability of the authority to meet its liabilities over the short and long run.

It is anticipated that the national financing authority's liabilities will in the first instance be secured by debentures providing a charge over council general revenues. Any additional credit enhancement from participants (such as through the provision of risk capital or guaranteeing the authority's obligations)—or from other tiers of government—would have the potential to enhance the likelihood of being assigned the best possible credit rating.

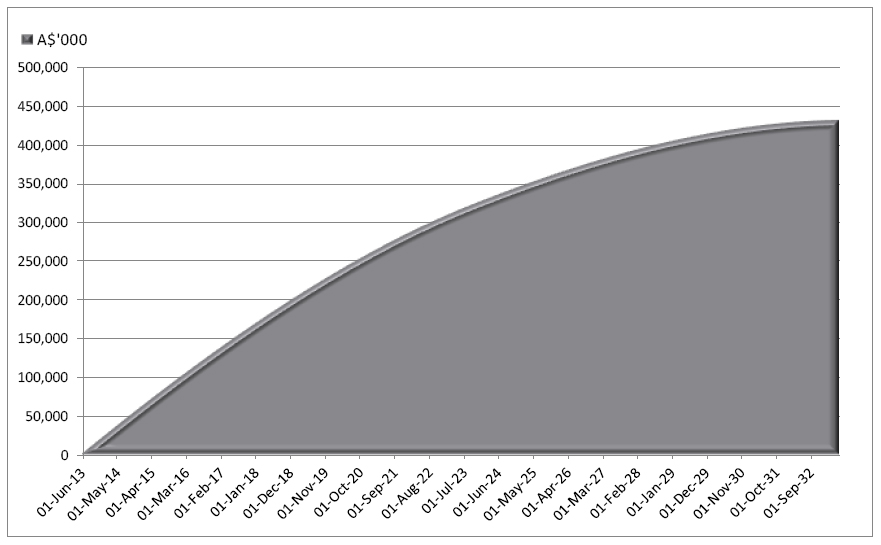

The liquidity of the products issued by a national financing authority is an important consideration and impacts on the appetite for, and pricing of, those products. A core role of the management of the national financing authority would be the management of liquidity, which would require sustaining sufficient volumes of ‘benchmark’ product in the market. The implicit assumption made is that the debt requirements of the local government sector are large enough to support a market for such debt instruments. As discussed in Appendix C, this report estimates a total debt requirement for the sector in excess of $10 billion. While this is a small amount compared with state and federal government bond programs, a take-up rate across the sector of about two-thirds is likely to support parcels of bonds large enough to attract institutional investors who hold (and trade) portfolios of similar products.

By way of comparison, two smaller states—Western Australia and South Australia—continue to maintain relatively small scale bond programs. Excluding short term paper, these programs over the last decade have had outstanding amounts as low as $7.5bn and $3.5bn respectively.

4) Advisory services

The national financing authority would provide advice to its members on the process for accessing debt and related financial products, and other matters related to capital structuring.

The key features of the authority's function as an advisor would be:

- Capacity building: the advisory role will complement capacity-building initiatives and provide an additional resource for councils to enhance budgetary discipline and financial sustainability.

- Addressing the reluctance to borrow: the provision of sound advice to the local government sector will enable the authority to become a counterweight—without vested interest—to voices driving the observed debt aversion.

- Market confidence: resourcing the authority with market experts and independent experienced individuals will be necessary to give the market confidence in the entity and ultimately expand the range of willing investors.

- Preserving council's core responsibilities: the advisory role must not replace the responsibility held by every council to prioritise and select infrastructure projects and appropriate procurement models in house.

It is anticipated that the focus of the advisory services provided by the national financing authority would be upon credit assessments, debt management and financial products. The focus would not be upon procurement models, prioritisation processes and asset management. As recommended in Strong Foundations for Sustainable Local Infrastructure, there remains a pressing need for an advisory body and guidelines for local government in these areas, but we suggest that the two advisory functions are discrete.

- Profitability and operating costs

The national financing authority would be created for the benefit of the community. Its role would be to minimise finance costs for the local government sector and not to make accounting profits.

Were a surplus to be made, it would be retained by the entity to build its capital base and subsidise auxiliary services. Depending on the model, a portion of the surplus could be returned to shareholders.

In the absence of the motive of profit, the national financing authority must still be incentivised to keep its cost base as low as possible in order to pass on the largest possible savings to its members. Pooled financing should lead to processing and issuing costs that are considerably lower than if the individual councils were to borrow from the capital markets on their own.

Other operating costs should be kept to a minimum. To this end, they could be benchmarked against comparable entities and performance indicators could be incorporated into annual reporting and management remuneration.

2. A national financing authority for local government

This section summarises the evaluation of options undertaken and describes the key features of the preferred model.

The detailed options evaluation is included in Appendix B.

Options

In this study, we identify 11 options for a potential national financing authority for local government in Australia:

| Explicit credit support by the Commonwealth or states/territories for capital raising | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Prescribed Commonwealth agency, with a Commonwealth guarantee over the agency's obligations |

| 2 | Entity established by the states and territories, with a guarantee provided by the states and territories over the agency's obligations |

| 3 | Entity established by a group of councils, with a Commonwealth guarantee over the agency's obligations |

| 4 | Entity established by a group of councils, with a guarantee provided by the states and territories over the agency's obligations |

| 5 | Entity established by a group of councils with a capital contribution from the Commonwealth and/or states/territories as a collateral against default |

| No explicit credit support by the Commonwealth or states/ territories for capital raising | |

| 6a | Entity established by a group of councils with a capital contribution from participating councils as a collateral against default |

| 6b | Entity established by a group of councils with a capital contribution from participating councils and an uncapped mutual obligation to support repayment of debt |

| 6c | Entity established by a group of councils with a capital contribution from participating councils and a capped mutual obligation to support repayment of debt |

| 7a | Entity established by a group of councils without any capital contribution but an uncapped mutual obligation to support repayment of all debt |

| 7b | Entity established by a group of councils without any capital contribution but a capped mutual obligation to support repayment of all debt |

| "Pass-through" model | |

| 8 | Entity established by the Commonwealth and/or states/territories as a financial intermediary to collect demand for specific-purpose borrowing and issue securities to match exactly these needs |

10 of the 11 options meet all the "core" functional requirements with respect to fund raising and lending to councils set out in Chapter 1. Each option is distinct by virtue of different permutations of factors relating to:

- ownership/ establishment

- the providers of any credit enhancement

- the nature of any credit enhancement.

The final model (Option 8) is a "pass-through model", and as such does not meet all the "core" prerequisites previously identified. This option would involve the establishment of a vehicle to act as a financial intermediary or arranger of debt for participating councils requiring finance for specific projects or programs. It would react in response to demand and not have a regular presence in the bond market.

The options are described in more detail in Appendix B, and—where relevant—appropriate precedents are referenced.

Evaluation criteria

The role of the evaluation criteria is to provide a basis for differentiating between the options. While many of the concepts and practical administration considerations are common across all the identified options, there are important structural and ultimately commercial differences.

The following criteria are used in the evaluation of options for a national financing authority and are based upon the motives for action previously described. The criteria address the key success factors around purpose and function, impacts on other governments, market credibility and participation rates.

| Purpose and function | |

|---|---|

| I | Capable of reducing the costs of debt finance. |

| ii | Capable of positively affecting the culture of debt aversion, supporting the sustainable use of debt and the transition to long-run sustainable financial management in the local government sector. |

| Impacts on other governments | |

| iii | Manageable upfront, and ongoing, impacts on the existing legislative and regulatory frameworks in the states and territories. |

| iv | Manageable upfront, and ongoing, impacts on the existing relationships between the tiers of government. |

| V | Manageable upfront, and ongoing, impacts on the long-run financial position of the Commonwealth, states and territories. |

| Market credibility | |

| vi | Capable of achieving an acceptable level of financing risk by attracting local (and international) debt market investors. |

| Participation rates | |

| vii | Capable of achieving a broad base of participation across the local government sector. |

Preferred option

The detailed evaluation of all models is in Appendix B. The evaluation suggests several models are closely ranked. This outcome largely reflects the broad similarities among the commercial characteristics and structure of the options. However, the evaluation process suggests that marginal differences in the credit support structures and the proxy to councils could have a significant impact on stakeholders and processes. The evaluation focuses on testing those impacts.

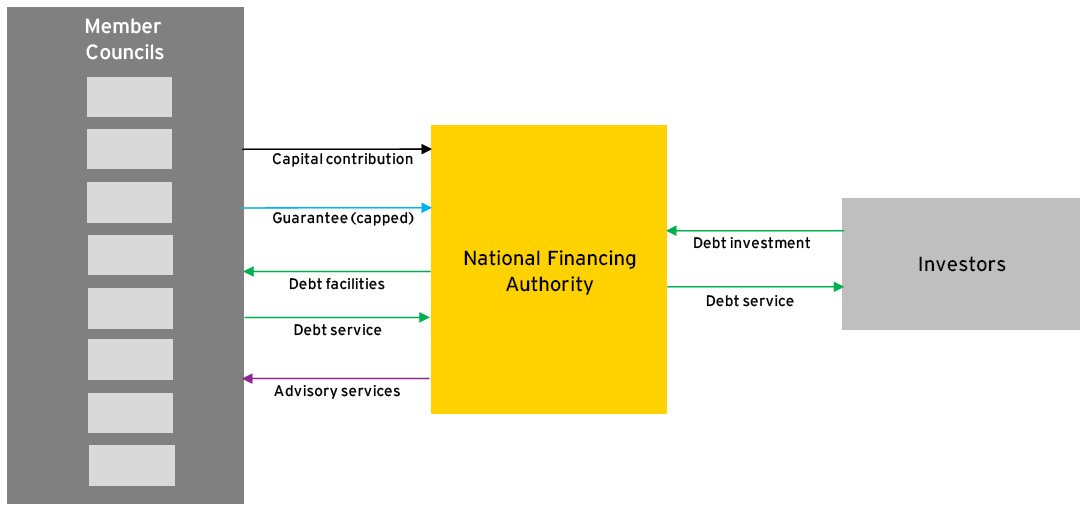

The highest scoring option overall is 6c. This option consists of an entity established by a group of councils, with the membership required to contribute an upfront capital sum and enter into a mutual obligation in support of the entity. This obligation would be capped at a level broadly proportionate to members" borrowing or financial position and would be secured against their revenueraising powers.

As with all options identified, the potential financial benefits, for those entities which borrow, include lower arrangement and servicing costs. The potential economic benefits include a higher rate of investment in priority projects which produce net economic, social and/or environmental benefits. With reference to the specific characteristics of Option 6c, the following factors (in combination) were crucial in differentiating it from other options:

- Cost-effective debt finance

The option has the potential to achieve pricing outcomes which represent material savings compared with the estimated borrowing costs of many councils.

The security features of this model could attract sufficient appetite to drive beneficial pricing outcomes.

In particular, this option requires local government to assume responsibility for the obligations of a new entity without explicit recourse to the next tier of government. It seeks to make efficient use of the implicit support for local government from state and territory governments, which is typically inferred by commercial lenders.

- Promoting a culture of sustainable debt use

The option could contribute positively to promoting a culture of sustainable debt use.

It creates a strong incentive for councils to form collectively to achieve the scale and function within a new entity which can drive pricing outcomes. This is a critical point of difference because a central objective of this study is addressing the observed sub-optimal use of debt. While other options arguably present a higher probability of achieving competitive financing, focussing exclusively on cost and not the broader rationale for providing the sector with its own channel to debt finance could jeopardise the overall benefits of intervention.

The option, as a council-established entity run with a strong collective ethos and sense of ownership, is aligned with the culture of the sector and consistent with sector-wide initiatives to improve long-run financial management. As noted in Strong Foundations for Sustainable Local Infrastructure, this could create a virtuous circle as more councils improve internal processes to manage the risks of borrowing and in-turn lower credit margins for all members and further spread the consequences of a default.

- No explicit support from other tiers of government

This option does not require explicit credit support from other tiers of government and is unlikely to require substantial legislative change. These are important factors in measuring the cost—including time—and risk inherent in a subsequent implementation process.

Two key risks are identified with this option:

- Building market credibility

The process of building understanding within wholesale funding markets of the nature and robustness of the structure for securing financial obligations and creating attractive financial instruments for investors may be relatively complex compared with some other options. There would need to be a balance struck between security and pricing, and between capital contribution and joint guarantee.

- Participation levels

Consistent with all options, the actual level of interest from individual councils is a key variable which is hard to forecast.

A particular consideration with the preferred model is that—given that lower interest rates cannot be guaranteed in advance—there would need to be sufficiently strong incentives for councils to make upfront capital contributions as a precursor to participation in the authority. This would be a function of the confidence of councils in the potential of the organisation to provide future benefits in terms of pricing, security and access.

As explored in Chapter 3, this may be mitigated by securing pre-establishment commitments from councils and a shadow credit rating from ratings agencies, to build confidence in the organisation's long-term viability.

Preferred option—key features

Although we have not developed a detailed specification for the authority, the following features and considerations are likely to be important.

- The authority would be an incorporated entity established by the local government sector and would operate under a voluntary membership arrangement.

- Each member would be required to provide a minimum amount of capital which could for example be proportional to average rates revenue. Capitalisation of the authority would serve to fund establishment costs, cover any net losses in the early years and meet capital adequacy requirements.

- Each member would be required to agree to a mutual guarantee over the authority's liabilities, which would be capped in proportion to its financial position.

- There would be no explicit credit enhancement provided by the Commonwealth, states or territories.

- The authority would aim to achieve the best possible credit rating, which would be based upon the combined creditworthiness of participating councils, strong integral liquidity arrangements, the mutual guarantee provided by members, and the implied support of the local government sector by other tiers of government.

- The liquidity and mutual support provisions would ensure that the likelihood of step in by state/ territory governments would be extremely low, thus minimising the amount of financial risk that states/ territories would have to take on in return for their continued implied support of the local government sector.

- The authority would build a presence in the bond markets and issue debt securities to raise funds.

- The authority would provide targeted debt products to its members at cost-effective interest rates and with flexible terms. It would develop a suite of policies to govern access to lending based upon the capacity of each applicant to repay the amount of debt sought.

- The authority would provide advice to its members on the process for accessing debt and related financial products, and other services related to councils" capital structuring.

- The authority would be incentivised to keep its cost base low, rather than to achieve a profit.

The features outlined above are designed to provide the starting point for a model which has the ability to develop market credibility without the need for explicit credit enhancement from jurisdictions or the Commonwealth. From a market point of view, the establishment of a national financing authority as recommended is anticipated to have the following features. - Councils have a high quality credit profile given the ability to raise rates revenues to meet their cash flow expenditure. Such a characteristic gives comfort to lenders as this provides an enhanced ability to meet debt repayment commitments compared to other types of non-government entities.

- The credit profile of individual councils would be strengthened by the diversification benefits of pooling the cash flows under the proposed authority structure. Overlaying a mutual obligation amongst the individual borrowers would further enhance the credit profile of the borrowing entity.

- With a strong credit rating, the authority could attract a pool of lenders to fund its requirements, from banks (domestic and international), super funds and (potentially) retail investors.

- Current levels of activity in debt markets present an opportunity for the authority as many banks have capacity to lend and requirements to comply with Basel III regulations which encourage them to lend to higher rated entities. Similarly, super fund and life fund investors (fixed interest) are also seeking long-term investment opportunities to place debt.

- From a sector point of view, the benefits of participation in a national financing authority with the features outlined above would differ from council to council based upon a number of factors, including the current lending arrangements in different jurisdictions. These are summarised below.

| Jurisdiction | Overview of current arrangements | Impact of the national financing authority |

|---|---|---|

| New South Wales |

|

|

| Northern Territory |

|

|

| Queensland |

|

|

| South Australia |

|

|

| Tasmania |

|

|

| Victoria |

|

|

| Western Australia |

|

|

3. Next steps and implementation considerations

This section includes a discussion of the potential next steps with regards to developing the preferred option further and considering issues around implementation. Moving to the next stage of development will need a concerted effort by all tiers of government. In New Zealand, where it could be argued that the political landscape is easier to navigate on account of its two-tier system, three years were needed to progress the Local Government Funding Agency from a concept to reality.

Broadly, the next steps for this initiative should be:

- policy consultation with federal, state and territory stakeholders

- further commercial and legal investigation of the preferred option, including consultation with the local government sector to test demand

- identifying commitments, costs and resources to move into the ‘build’ phase.

1) Policy consultation

Developing the momentum for a national financing authority will be a function of the degree of consensus among federal, state and territory governments. This consensus primarily relates to accepting the case for action and the substance of the solution.

For these reasons, it is suggested that policy authorities consider using a coordinating body such as a COAG Ministers" Forum to prepare a consensus policy position.

It is anticipated that the main areas of discussion will be:

- Level of participation

The optimal size of a collective vehicle—or the ‘tipping’ point at which membership is sufficient—is that which creates enough issuance to drive strong competition for the entity's securities and moves pricing to a point comparable with similar and equivalently-rated products.

There is likely to be a relationship between policy consensus and the level of participation by councils, which is a critical enabler of competitive pricing and credibility in financial markets. Consensus may not need to be unanimous, but without broad agreement, the risks to patronage would probably be unacceptable.

- Impact on existing borrowing arrangements

Many councils have long-run relationships with incumbent entities—for example, the Queensland Treasury Corporation or the Local Government Finance Authority of South Australia.

The size of borrowings in the local government sector may not be large or diverse enough to accommodate a new national financing authority which operates alongside these existing arrangements, especially in the early days of its operation.

In light of this, strong signals from the Commonwealth and state governments about their perspective on a collective borrowing vehicle would be important to build credibility and market confidence. To enable the proposed entity to establish itself and be effective, the states and territories may need to consider making a commitment to stepping back from their role as the ‘one stop shop’ for non-private lending.

2) Further commercial and legal investigation

This study is preliminary in several areas, and has not had the benefit of close access to stakeholders. To progress the investigation of options, the assessment in this study should be validated in the context of updated information and discussion. In particular, the commercial structure of the preferred option(s) needs to be further developed so that it focuses on the role and function of the entity, the risk allocation between investors, intermediaries and borrowers, and the credit risk related to lending to the authority. These aspects are explored below.

- Role and function

Further assessment should be made of the services which offer benefit to local government as borrower. As discussed in Appendix A, the role of a collective vehicle is to service the needs of local government by procuring debt finance and conducting a credit risk assessment, but the functions could be more broadly defined to include an educative function and ad hoc financial advice related to borrowing. The value of these services, and a more precise understanding of need, could be further tested with councils.

- Risk allocation

There are several areas of risk allocation which should be further investigated. The most important is patronage risk, or the rate of usage of a collective vehicle by councils. A number of assertions have been made in this study which could be tested further with representatives from the sector, primarily their view of its value and the key factors in their assessment of the benefits of membership.

This could be achieved through a structured questionnaire and consultation process, which could be used to poll, for example, 100 councils of differing characteristics across Australia. This process could also be used to raise awareness of the concept, which may be low despite the precedent overseas including recent developments in New Zealand, the UK and France.

The key commercial factors likely to be identified include the willingness to participate as credit enhancers, through providing capital funding or a guarantee in respect of financial obligations. As noted in the evaluation in Appendix B, there is likely to be a process within councils of analysing the net benefit (or cost) of participating as a guarantor but receiving margin and transaction cost savings, as well as control of the entity through the membership.

- Credit risk

The key risk for investors will be the capacity of a national financing authority to honour its financial obligations. As discussed through this study, this risk can be mitigated by issuing financial instruments enhanced by protection against arrears or defaults on either individual loans or financial distress within individual members.

The implementation process would benefit from testing perceptions of the strength of the protection implied in the preferred option with potential investors such as wholesale funding market participants, primarily local and international banks and fund managers. Our preliminary engagement with market participants has indicated that an appropriately-structured national financing authority would be well-received and there would be appetite for bonds issued by it. However, it would be worth testing this further as the preferred model is developed, possibly through a structured questionnaire and interview process.

Alternatively, assuming there is a level of consensus about the preferred option and a broad—albeit indicative—level of interest within councils, a preliminary rating process could be used. For example, the New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency engaged the ratings agencies to assign a "shadow" credit rating prior to going live, and this was an important step in building market presence and credibility.

Completing either process would add substantially to the level of confidence in the initial rate of patronage and the ‘steady state’ rate (noting that participation in the authority would increase as the organisation builds credibility over the medium-term and demonstrates the robustness of its credit fundamentals).

Accounting considerations

The accounting treatment of participation by councils in a national financing authority will ultimately reflect the substance of the commercial arrangements attached to membership. Without knowing the precise nature of those commercial arrangements, it is too early to offer a view on the impacts for financial reporting by councils. However, some important considerations are addressed below.

- Each member council will be responsible for repaying its own debts, meaning these amounts are likely to be recognised as debt on their balance sheets in accordance with AASB 132. It is important to be clear that the authority is not a means of shifting recognition of debts from local government.

- The treatment of the mutual guarantee in the preferred option would depend, among other factors, on the likelihood of it being exercised. Depending on the terms of a general guarantee, it could be treated as a provision on balance sheet under AASB 137 or, where payment is considered remote it could be treated as a contingent liability requiring disclosure only. Guaranteeing the performance of a specified debt—as opposed to an authority's obligations—could be a financial guarantee under AASB 139 and accounted for as a liability.

- The consolidation of a national financing authority is also important to consider from a balance sheet perspective. Again, depending on the final structure of the entity, it is possible that members could need to consolidate part of the authority. A key test in this respect is who has management powers for the authority and who benefits from the variable returns from operations. If there is no requirement for consolidation, then membership could be considered a joint venture under AASB 11 or equity accounted as an associate. A key test with respect to joint ventures is whether management powers and decision making are contractually shared.

- A national financing authority is likely to enter into hedges to manage the interest rate exposure. If hedge accounting is to be used, there are accounting requirements for documenting and monitoring of hedges, and it will be important to ensure member councils understand any risk exposures in this regard.

- Legal review

A legal review would complement the review of commercial parameters. The purpose of a legal review is to test assertions in this study in relation to:

- the extent of legislative change required in the states and territories—this would involve a review in each jurisdiction of the current framework and whether it explicitly allows or disallows the type of arrangements which member councils would need to form with a collective vehicle, including the associated legal risks

- the powers required by a collective vehicle to deliver its purpose, and the implications for the corporate form of the entity

- the powers which councils would need to enter into the proposed entity and the associated legal risks

- laws and regulations to which a collective entity would need to comply to fulfil its stated purposes, and the implications for corporate form.

Aspects of this review would be expected to address interpretation of laws and regulations and represent legal advice. Accordingly, the scope of the review could be tailored to the level of definition of the commercial structure of a preferred option. A critical part of this work is likely to be an analysis of the amendments to legislation required to allow councils to establish and participate in a collective vehicle. There are clear benefits in avoiding substantial amendments to the extent possible, because the venture would be less likely to be delayed in political processes.

A legal review may also be useful for engaging the local government sector on the form and content of the contractual instruments likely to be required by the preferred option. This includes for example debentures over rates revenue or an undertaking to provide a capped or uncapped guarantee to the entity in respect of its financial obligations.

3) Commitments, costs and resources

The costs of establishing the entity would be material and early consideration of funding them would be prudent. Costs include management, operational and advisory personnel and training, systems and equipment, and transaction costs. Precedent models suggest these costs could be several million dollars.

There are several ways in which establishment costs could be funded, and these options should be identified at an early point. A contribution across the tiers of government may, for example, be part of the process of reaching consensus on a way forward.

The approach to funding establishment costs requires consideration because it could impact on appetite and patronage. For example, to the extent that these costs are to be recovered from members, there may be a perception that ‘early movers’ would pay a disproportionately larger share, which could deter membership. Further, there may be a case for creating incentives for membership by shifting or deferring the members" share of establishment costs.

Appendix A—A national financing authority in context

Local infrastructure

In Australia, all three tiers of government share responsibility for planning, delivering and maintaining public infrastructure.

Local government is responsible for a stock of assets most recently valued at over $300bn, which it is required to maintain to a minimum quantity and quality to fulfil its legislative mandate to local communities.1

Council-provided infrastructure is the backbone of our communities and our regions. It provides access to welfare, education, transport, sport and recreation. It serves key environmental functions, such as waste collection and disposal, and enables services to be produced and consumed in the community by residents, workers and visitors.

Providing and maintaining this infrastructure is one of the most important responsibilities faced by Australian councils. It also presents one of their largest challenges.

Underinvestment in the right infrastructure results in constrained economic activity, reduced amenity for communities and declining social equity. But the costs of infrastructure are high and lumpy, and at a time when there are many competing demands on revenues, meeting these costs places significant pressure on council budgets.

Together, the Commonwealth, states, territories and councils have a duty to ensure this challenge is addressed and that essential infrastructure is delivered.

Strong Foundations for Sustainable Local Infrastructure

In June 2012, the Minister for Regional Australia, Regional Development & Local Government released Strong Foundations for Sustainable Local Infrastructure, a review undertaken by Ernst & Young that examines how local government plans, finances and delivers infrastructure investments.2

The 13 recommendations contained within the report are designed to provide a way forward for the local government sector to make the most of the tools and levers it already has, while at the same time to be open-minded to new ways of doing things. The focus is on ways in which councils can get more infrastructure from existing funding sources and the recommendations cover three broad areas:

- enabling councils to leverage existing funding sources for investment in new infrastructure

- improving councils" access to cost effective finance

- improving councils" ability to identify and develop infrastructure and gain access to specialist skills necessary to deliver innovative financing solutions.

The report was well-received throughout the sector and by key government stakeholders. Subsequent to the publication of the report, the Commonwealth has been active in assessing the merit and practicability of the recommendations. In doing so, it will require the cooperation of state and territory governments, local government peak bodies, councils and the private sector.

Borrowing for local infrastructure

Councils, like any project sponsor, must consider all the associated costs of delivering their infrastructure priorities. This includes the upfront capital spend and all ongoing expenses related to repair, maintenance, renewal and financing. All these future costs should be taken into account when deciding whether or not to commit to any project.

It is the capital for upfront expenditure, however, which generally presents the largest challenge. This is because infrastructure is by its nature capital-intensive and there is almost always the need to raise significant funds at the beginning of a project to pay for the construction and commissioning of the asset.

There are many competing demands on councils" core revenue sources (primarily rates and grants). When core sources of funds are constrained in this way, access to cost-effective finance can be the difference between a project going ahead or not.

One of the central findings of Strong Foundations for Sustainable Local Infrastructure was that there is significant capacity within the local government sector to optimise its level of borrowing for the purpose of capital spend on infrastructure. Although there is a readily accessible pool of finance available to some in the sector, there is a demonstrable preference not to use debt as an appropriate method of paying for infrastructure. This in turn is having a negative impact on the infrastructure gap.

Provided that the ongoing costs of servicing debt are affordable, then the focus of project providers can be on the economic and social benefits of investing wisely in infrastructure.

Borrowing is a common feature of private sector capital structures and does not mean that a council is acquiring things it cannot afford. In the context of sound financial management and project planning, the key benefits of debt are that it can:

- enable councils to deliver new infrastructure when it is required and earlier than they otherwise would have been able

- enable councils to invest in the renewal and lifecycle costs of existing infrastructure, which are time-sensitive and if not delivered can increase the whole-of-life cost of an asset

- allow the smoothing of the payments for new investment over time

- allow the cost of infrastructure to be shared with future generations who will enjoy the benefit of the asset

- prevent the need to divert funds from internally-generated renewal and maintenance budgets to capital expenditure

- open the door to new sources of investment, for example from institutional finance providers, which bring additional rigour and discipline.

The consequences of the suboptimal utilisation of debt finance

Overlooking debt as a source of capital can prevent infrastructure investments from going ahead because councils often do not have adequate alternative sources of capital to fund projects with lumpy cost profiles. As a result, many councils prefer to wait until capital costs are funded (in large part by federal or state government grants), which can take years to secure.

The consequence of delay and non-investment is that the infrastructure gap (also known as the infrastructure deficit or backlog) gets bigger—or at the very least, it does not get smaller.

The infrastructure gap is essentially the difference between the required investment in infrastructure—on a forward looking basis—and the actual investment. It represents an acknowledgement that every council in Australia has identified priorities for its community which it is unable to fulfil.

Numerous attempts have been made to monetise the gap at all levels: council, region, state and national. While each attempt to quantify the gap uses a different methodology and results in a different answer, there is no doubt that the gap does exist and that, on an aggregated basis, it is very large.

Assessing the infrastructure task

The following reports are just a selection of the many studies in recent years that have focussed on assessing the financial sustainability of the local government sector and the implications of a growing infrastructure gap.

National: PricewaterhouseCoopers, National Financial Sustainability Study of Local Government, 2006

New South Wales: Local Government & Shires Association of NSW, Are Councils Sustainable?, 2006 (Allan Report)

South Australia: Financial Sustainability Review Board, Rising to the Challenge: Towards Financially Sustainable Local Government in South Australia, 2005

Tasmania: Access Economics, Review of the Financial Sustainability of Local Government in Tasmania, 2007

Western Australia: Western Australian Local Government Association, The Journey: sustainability into the future, shaping the future of local government in Western Australia (Systemic Sustainability Study), 2008.

This study does not attempt to quantify the infrastructure gap. This would be a significant undertaking, not least because the quality and standardisation of data and financial reporting across the sector is variable.

Although a substantial amount of work is underway in most states and territories to improve the level of knowledge of infrastructure, many councils are starting from a low base and even those with more sophisticated systems and processes acknowledge material gaps in their understanding of the condition of their stock of infrastructure. By way of illustration, it is telling that the Australian Local Government Association (ALGA) has recently engaged consultants to run a pilot just to establish whether there is sufficient data and information to understand the state and condition of the class of asset—local roads—which is generally considered to be the best documented.3

Eliminating the infrastructure gap should not be the aim of a national financing authority—this will ultimately come down to the community's willingness to pay to do so and will rely on considerable effort by all tiers of government to support capacity building initiatives. A collective borrowing agency alone will not fill the gap, but could provide councils with the machinery to make significant inroads into it.

Despite the uncertainty around the precise size and composition of the backlog, at a minimum there is enough evidence of its approximate size to justify action by government to assist councils to address it themselves.

Without such an intervention, there remains a significant risk that capital investment over coming years will continue to fall well short of what is needed to meet the infrastructure needs of Australian communities.

The difference that cost-effective finance can make—case study

There is limited consistency in how state and territory governments facilitate local government borrowing programs. This means that the actual cost of local government debt finance varies significantly between states on structural rather than practical grounds.

New South Wales and Victorian councils, for example, predominantly borrow via commercial debt sourced from the banking sector, while Queensland councils predominantly borrow directly from the Queensland Treasury Corporation (QTC).

Consultations with some of the financially stronger New South Wales councils highlighted that while availability of bank debt had not been an issue, recent pricing had been a significant deterrent in assessing a number of infrastructure enhancement opportunities.

One example noted was based on upgrading a range of sporting facilities. The package of upgrades was forecast to generate additional council revenue in the medium-term, but the short-term debt costs were judged to be too high for council to accept the cash flow risks. It was noted that a reduction in debt costs of just 50 basis points would have provided the headroom for the upgrade to be implemented. The project did not qualify for interest payment assistance under the Local Infrastructure Renewal Scheme (LIRS).

Barriers to optimising the use of debt finance for infrastructure

Strong Foundations for Sustainable Infrastructure found that the flow of debt financing into the local government sector is constrained by:

- a lack of financial expertise and capability

- the costs of debt (finance costs and administrative obstacles)

- the absence of structured local government debt products suitable for institutional investors.

The consultation undertaken revealed that the reluctance to borrow is often informed by a perception that the community regards a low debt position as a reflection of sound fiscal management. It does not appear to be widely understood that, in fact, a low debt position means that current ratepayers are meeting the full cost of infrastructure assets, while in reality much of the benefit will actually be gained by future generations.

This is compounded by overly pessimistic views of financial risk and the probability of distress, which is not consistent with historical evidence of local government default.

Debt will always have associated costs and risks. These costs include not just interest payments but transaction costs and complicated processes and due diligence requirements. They are costs and risks however, that can be mitigated through responsible financial planning and through taking advantage of the availability of secure and competitively priced debt products. They are costs and risks which must be weighed up against the upside of being able to deliver or bring forward key infrastructure priorities which might not otherwise have been possible.

Decisions about whether to take out borrowing facilities will remain a question for individual councils based upon the relativity of the benefit of the project and the ability to meet the payments associated with it (see below). These decisions should be informed not by a cultural reluctance to borrow, but by a considered assessment of the costs and benefits of alternative financing solutions.

How indebted is local government and what is the optimal debt load?

Levels of indebtedness, regardless of the source of debt, are very uneven across the sector. As a general rule, however, Australian councils continue to adopt a cautious approach to borrowing for infrastructure. There remains a clear preference to use current year funding in the form of rates and grants receipts for this purpose, rather than utilise debt finance to match the incidence of the costs to the benefits, and ensure that current ratepayers are not shouldering a disproportionate burden.

A number of local mayors write with pride in their annual reports that they have succeeded in reducing their levels of debt to zero.

Queensland Treasury Corporation reports that 22 of 73 councils in the state have no outstanding debt at all. Indeed, many councils (a third of councils in South Australia, for example) have negative indebtedness—that is, their financial assets exceed their borrowings. The Tasmanian Auditor-General recently concluded that "in almost every case, councils" financial assets exceed total liabilities indicating they are in strong positions to meet short-term commitments and there is a capacity to borrow should the need arise."4

It may be that these councils are successfully managing their infrastructure backlog and have no need for additional expenditure; however this seems unlikely in light of the findings of a multitude of independent reports in almost every jurisdiction indicating that capital expenditure on existing assets is significantly less than what is required. Indeed, consultations with state governments carried out during this study have suggested that there are numerous cases of councils that are maintaining zero debt policies while at the same time having low infrastructure renewal ratios.

Indebtedness of Victorian councils

As part of the annual report on local governments in the state, the Victorian Auditor-General conducts an analysis of councils" indebtedness. The analysis looks at non-current liabilities (mainly comprised of borrowings) as a percentage of own-sourced revenue (as opposed to financial gearing where debt is generally compared to net assets):

In 2011, the Auditor-General concluded that in relation to indebtedness, only 3% of councils are at high risk (defined as "potentially long-term concern over ability to repay debt levels from own-source revenue"), with 10% at medium risk ("some concern") and 87% at low risk ("no concern"):

The most recent ABS data (from 2010—11) shows that, nationally, debt represents only 2.8% of net assets at the local government level, and that interest payments represent 1.4% of total council revenue.5 This suggests that there is greater capacity to service borrowings.

| NSW | NT | QLD | SA | TAS | VIC | WA | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gearing ratio (Bank debt/ net assets) |

2.5% | 0.6% | 4.6% | 3.8% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 2.5% | 2.8% |

| Debt servicing ratio (Interest expense/ total revenue) |

1.9% | 0.2% | 1.8% | 1.6% | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 1.4% |

Optimising the use of debt is not to say that every council should be seeking to increase its borrowings and financial gearing. There is no right or wrong level of debt, and there is considerable debate about the definition of a sustainable level. Indeed, the Nationally Consistent Frameworks on local government financial sustainability, which were introduced in 2007 to provide a set of aspirational principles and best practice guidelines, recognised the limits of tightly-defined indicators which "individually and without associated explanations … can only ever tell part of the story".6

A future national collective lending vehicle would—as discussed in this report—be able to apply similar restrictions on members, if it were deemed appropriate.

Do councils have the capacity to borrow more?

The noticeable improvement in asset management techniques in recent years is providing councils (both elected members and officers) with a better appreciation of whole-of-life

costs associated with infrastructure. It has been observed that this is leading to a greater awareness of the implications of unduly low levels of debt upon councils" ability to invest in their assets.

A recent practice note issued as part of the Commonwealth's Local Government Reform Fund (2012) stated that "many councils have very low levels of net financial liabilities (debt and other liabilities less financial assets) relative to their revenue levels and the level of infrastructure assets they manage. A soundly based long-term financial plan can highlight the affordability and impact of additional borrowings (e.g. to address warranted but otherwise unachievable asset renewal). A modest increase in borrowings to fund priority needs would typically add materially very little to most councils" total operating costs. While organisations should not borrow unless necessary to satisfy their objectives, they should also not be averse to borrowing where this is warranted, to provide cost effective and affordable, desired levels of service."7

Within the limits of any restrictions which may be placed on councils" net borrowing, ultimately the capacity to raise debt will be a function of the capacity to fund debt servicing payments for the term of the loan, and to repay the principle once the term has expired. The availability of finance will always be a secondary consideration to the availability and application of funding.